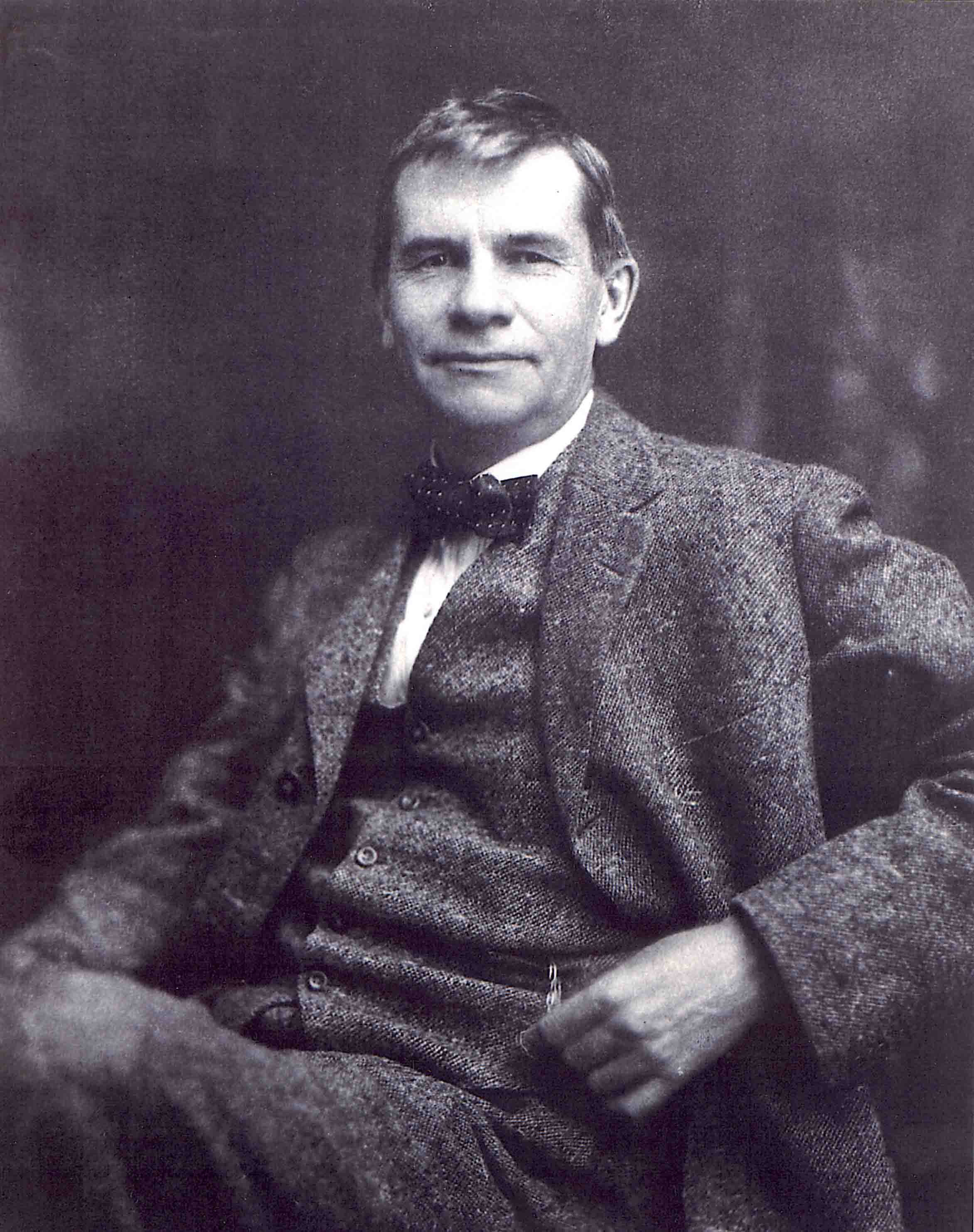

GUSTAV STICKLEY (1858-1942) so synthesized, romanticized and popularized the Arts &

Crafts style of architecture during the first two decades of the last century

that today the style is known generically as "Craftsman."

However, only a house originating from plans published by

Stickley through his magazine The

Craftsman can be a true Craftsman Home. He published descriptions and drawings of homes in this

magazine beginning in 1901. In the January 1904 issue, he featured the first

official Craftsman Home and announced that henceforth the magazine would

feature at least one house a month, and subscribers could enroll in the "Home Builders Club" and could send away for a set

of plans for one house from the series per year, free of charge.

These Craftsman plans offered the average American family a

house that was a home, based on the bedrock virtues of beauty, simplicity,

utility and organic harmony. Stickley believed that the "nesting

instinct" was "the most deep-seated impulse" of humankind. He

wrote in the magazine: “The word that is best loved in the language of every

nation is home, for when a man's home is born out of his heart and developed

through his labor and perfected through his sense of beauty, it is the very

cornerstone of his life.” He intended in his home designs "to substitute

the luxury of taste for the luxury of costliness; to teach that beauty does not

imply elaboration or ornament; to employ only those forms and materials which

make for simplicity, individuality and dignity of effect." Today we are left with an unexplored legacy.

Stickley's furniture has been researched and the findings presented in many

books and articles, but his architectural contributions have yet to be fully

examined. Perhaps this is because collectors whose passion is furnishings have

yet to try collecting the ultimate Arts & Crafts piece—the piece everything

was designed to fit into—a Craftsman Home.

How do we recognize a Craftsman Home?

Like a piece

of Stickley furniture, a Craftsman Home has refinement of design and quality of

construction and finish.

It is

often site related and placed to advantage using the site.

The house

is built with materials found on the site, and/or natural materials native to

the region.

As with

Stickley's furniture, the house designs rely on exposed structural elements for

decorative details. The variety of natural materials provide textures for light

to play on.

Voids—in

the form of recessed porches and entrance ways—and terraces and pergolas,

create visual interest.

Interiors

emphasize form and function. Space is conservatively and creatively used for

living, with design elements utilizing wood and built-in spaces such as

inglenooks, benches and cabinets.

Light

fixtures and hardware relate as design elements.

This philosophy and these decorative details were expensive to

execute. Consequently, although the homes were idealistically conceived for the

masses, they were built primarily by the middle class. They used Stickley's

Craftsman Home plans, and many modified them to suit their tastes and

requirements. These homes were not “kit” houses like those sold by Sears,

Roebuck and Co. and Aladdin Homes, but were always built by local builders

chosen by the owner, from these plans sent through the mail by Stickley’s firm.

How many of these houses were actually built?

Stickley designed at least 254 homes and published 226

plans. He expended great effort promoting them, publishing a number of

promotional pamphlets and at least two books, Craftsman Homes and More

Craftsman Homes. [These books are available in inexpensive, quality reprints

from Dover Publications.] While some of the house designs were featured in

these promotional books, the only existing source for ALL the plans is Stickley’s

Craftsman Homes, published by Gibbs-Smith and now out of print, but

available used.

We do not know how many were actually built but believe that a

great many were built across the country. We speculate that the educated middle

class built them and that they will be found mostly in areas around cities

where the first suburban expansion took place. In larger cities they will be

found in areas serviced at the turn-of-the century by commuter railroads and

street cars. They will also be found in towns with universities or art

communities.

Who designed them?

We don't yet know for sure who designed the Craftsman houses.

There are many different drawing styles in the magazine’s renderings,

indicating different draftsmen at work. Other than Harvey Ellis no staff

architects are listed on Stickley's payroll records, his furniture designers

and draftsmen are noted as being in the architectural department, and a few

architects appear to have been paid consultants from time-to-time. Of course,

there may have been a number of unlicensed architects among those draftsmen.

We do know from newspaper articles that Charles D. Wilsey was hired in March

1904 to head the new department, but he lasted only a few months. We also know

that Stickley hired George E. Fowler sometime in or before 1914 as an architect

and that when the company went bankrupt he was in charge of the department.

Nevertheless, considering Stickley's intense interest in the

project, it is safe to say that he had major responsibility for the designs.

Before he established his new business he traveled to Europe and

around the U.S., and he surely was aware of the various architectural styles of

Josef Hoffmann, C. F. A. Voysey and M. H. Baillie-Scott, as well as published

Will Bradley interiors and the houses of the Prairie School movement, led by

Frank Lloyd Wright. Also, Stickley appears to have been a "quick

read" and may have learned a great deal from his brief associations with

architects Henry Wilkinson, E. G. W. Dietrich and Harvey Ellis.

The house plans fall into four different periods

David Cathers, in his book, The

Furniture of the Arts and Crafts Movement, divides Stickley's

furniture work into periods. This system can be adapted to fit Stickley's house

designs:

•The

Experimental period is 1900-1903;

•The Detailed

Home period, 1904-1907;

•The Mature

period, 1909-1915;

•The Final

period, 1916.

The Experimental period, 1900-1903

From its beginning The

Craftsman published

house plans. Interior room designs began appearing in 1901, perhaps to display

the furniture in the proper setting. Stickley must have known that it did not

look good in the Victorian interiors of the time. The first house article was

called "The Planning of a Home" and featured a design by architect

Henry Wilhelm Wilkinson.

In the Experimental period The

Craftsman printed

suggestions for architectural details, although not always complete house

plans. The prototypical Craftsman House appeared, a suburban house "by the

United Crafts," in an article by editor Irene Sargent. The design of the

interior resembles the furniture—massive, plain and simple.

In early 1903, several houses designed by architect E. G. W.

Dietrich appeared and the term "Craftsman House" was first used. All

interiors, of course, showed Craftsman furniture. The relationship was being

established: the furniture and the houses go together into a new living

environment. The furniture was only part of a much broader picture—a new life

style.

During 1903, architect/designer/artist Harvey Ellis came to work

for Stickley and this brief relationship (Ellis died in 1904) strongly

influenced Stickley for the rest of his career. Ellis designed a line of

lighter, more art nouveau-looking furniture, and he wrote and drew extensively

in The

Craftsman. A series of very interesting conceptual houses by Ellis

were published during 1903, including a Craftsman Home (a suburban house), an

Adirondack camp, an urban town house and even a summer chapel and a farmhouse.

These designs were unlike anything previously published in The

Craftsman. After Ellis' death the overt influences gradually

disappeared, as Stickley reverted to plainer and more rectilinear designs. But

the use of the curve and other Ellis signatures continued to show up in the

furniture and houses.

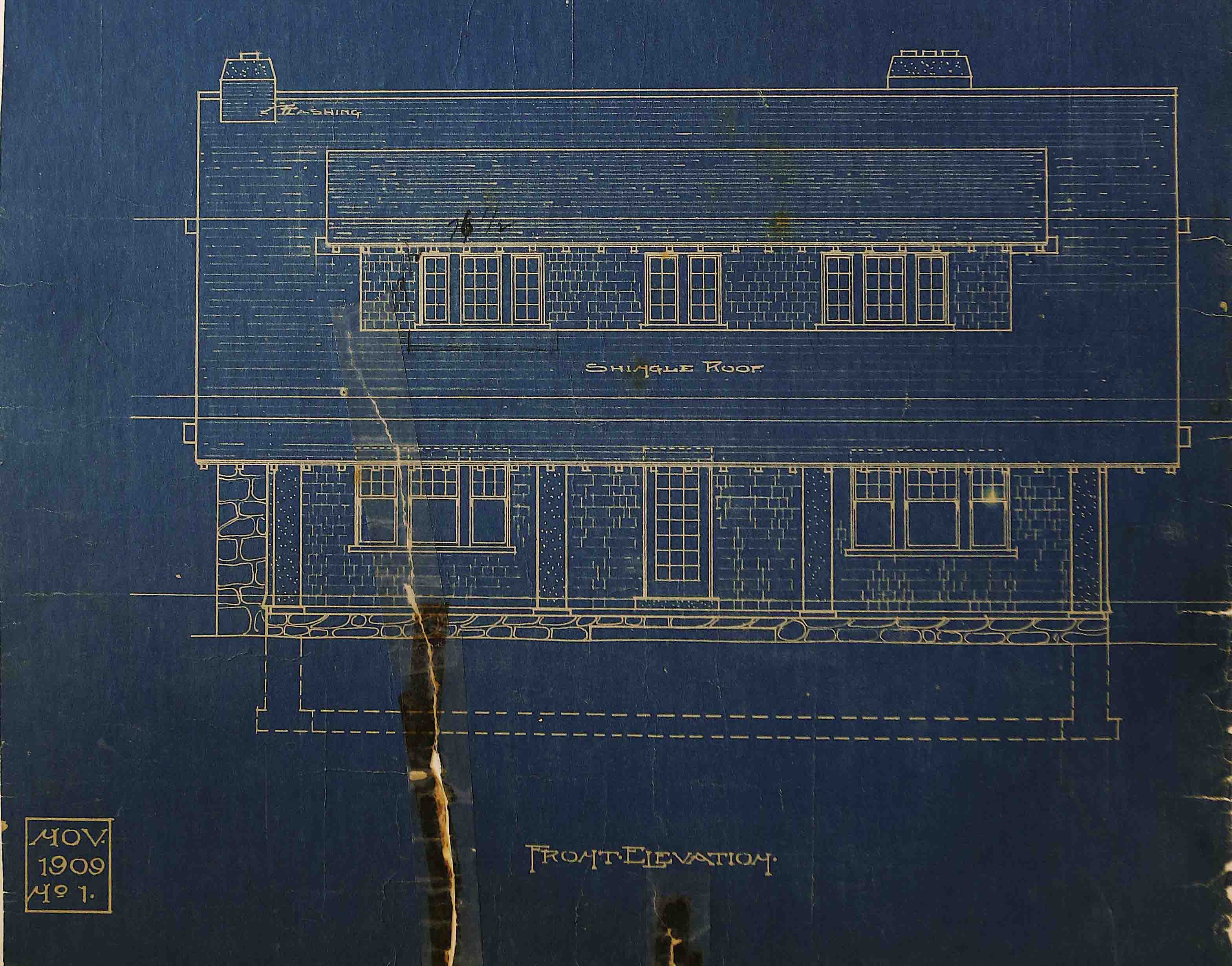

The Detailed Home period, 1904-1908

Stickley began to publish his own home

plans and offer them to readers of The

Craftsman. The houses were published at the rate of at least one a

month, although some months featured as many as three houses. In addition to a

sketch of the house, there were extensive details: elevation drawings of front,

sides and rear; floor plans; interior renderings of most of the main rooms and

details of woodwork and wallpaper designs. Even details of color combinations

of wallpaper, paint, rugs and curtains were given. Little was left to one's

imagination, and the articles at times ran ten pages or more. (Stickley sold

all accessories needed through his furniture catalogue and the magazine.)

After 1904, the houses were published for the life of the

magazine, except for two periods: The first break ended the Detailed Home

period and was from June 1907 to mid-1908, when Stickley was involved in

the purchase of Craftsman Farms and the setting up of a home building company called The Craftsman Home Building Co., with offices in New York City.

During that time articles on various cabins for Craftsman Farms appeared, as

well as the Farms' "Log House," which was originally designed as a

"Club House."

The Mature period, 1909-1915

In January 1909, the house designs resumed. These houses were more unified

visually—their style is consistent. Two homes were offered each month and only

an exterior rendering and one other drawing—an interior view or an exterior

detail such as a porch or sleeping porch—as well as floor plans were shown for

each house. The descriptions of the decor and color of these homes was minimal. The interior was often designed around a fireplace inglenook.

Stickley believed that the fireplace could be the center of indoor family

activity—the recreation room of today!

Midway through this time a slug appeared under the drawings

indicating Stickley as the “architect.” But as Stickley's economic decline

began, the articles became shorter and the interior drawings were dropped.

The Final period, 1916

Again, without editorial comment, the houses were dropped in

June 1915, for one year. They resumed in June 1916, one month after editor Mary

Fanton Roberts' article about Stickley's bankruptcy in the magazine and the

introduction of his Chromewald furniture line. This six-month period featured

the last set of Craftsman Homes. In the accompanying article, Stickley said

that he really felt that he had exhausted the subject but that reader demand

was forcing him to renew the project.

By this time Stickley was pretty much out of the picture and

whatever influence he had on these houses was indirect; the Architectural

Department had worked under his supervision and knew how he thought. His

compass mark and name were gone from under the house drawings and, instead,

"There are no 'Craftsman Houses' except those which appear in this

magazine" appeared.

These houses were probably designed by George Fowler, who along

with Roberts and the rest of the staff, founded The

Touchstone, when The

Craftsman finally ceased publication and was absorbed by the Art World magazine in December 1916. The reader

demand must have been high, because The

Touchstone continued

to offer "Touchstone Houses" designed by Fowler. Art World magazine acquired the back file of house plans and offered them to readers for a while, with the

addition of two new houses (Nos. 222 and 223), before reverting to reprinting

the already published plans. —Ray Stubblebine